How do you think about and plan your portfolio of projects when you’re part of an internal design team? It’s sometimes hard to spot achievements in my job. It can also be tricky to plan where I can have most impact.

Much of the work of an IA is relatively invisible. IAs spend their time exploring edge-cases, identifying and adjusting variables, mapping dependencies. It’s rarely sexy. It’s rarer still that the full scope of the work can be expressed in an interface. And there are lots of ‘hard slogs’.

I try to manage my workload and portfolio of projects so that I can have an impact in the short, mid and long term. And that I don’t get too tired or disillusioned along the way. I use three of my favourite diagrams to think about what I should be doing — and help the rest of the team plan their workload too.

Pace layers

Pace layers are easy to grasp and straightforward to communicate. Everyone can see that in architecture there are different layers and that these layers change at different rates. It’s even easy to relate this central idea to organisations and UX.

Jesse James Garret’s Five elements of user experience give you a simple set of layers to talk about the rate of change and re-evaluation of digital products and services. Layered technical architectural models also make it easy to talk about the rate of change or even costs of change at different layers. A re-skin is cheaper and probably quicker than a re-architecture.

Much of the job of an IA or UXA focuses on the slower-moving and more fundamental layers. It takes longer to have an impact at this level. It’s more complex. Dependencies tend to stack up on top of the lower layers, so there is more to consider and the rate of progress is often slower.

Pace layers helps to explain and justify why IA takes a long time. It also helps describe why it’s so fundamental. Get the foundation wrong and the whole design might fall down. Pace layers communicate the complexity of our work and justify the rate of work, change and impact.

Hard slogs

This slow rate of impact and change has dangers for a discipline. It’s sometimes harder to point at a long list of accomplishments as an IA. The IA is the foundation of the design. Lots of other more visible things sit on top of it.

The efficacy of the architecture might only be visible over a longer period too. The real value of a controlled vocabulary or scalable metadata strategy might only be revealed after years of content production. On day one or even day 60 it may be hard to judge the work with any degree of accuracy. So there’s the danger of visibility. How do we communicate what it is that we do and why it’s useful and necessary?

But I think there’s also a danger for our happiness. If IA is more full of hard slogs than quick wins, then do we miss the endorphin rushes from those regular achievements that we might notice in other types of project and discipline? I think this danger might increase the closer the IA gets to long term strategic planning. The work is harder and more complex. The progress is slower. The constraints and dependencies are sometimes more entangled and intractable. How do you stay sane with a portfolio of projects like that?

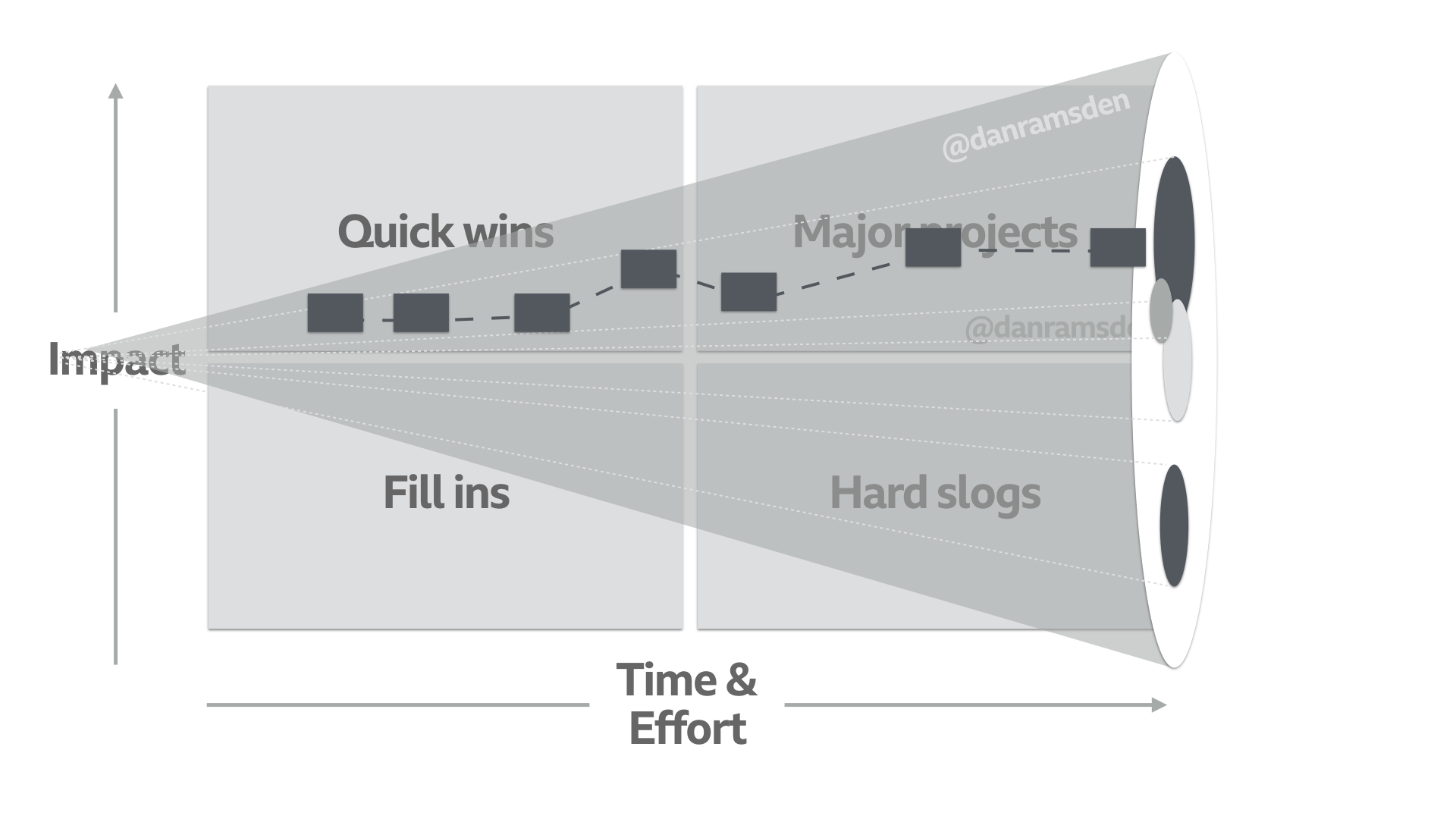

I prioritise. And I do it based on two criteria.

Firstly, I identify the projects that need lots of effort — the hard slogs and major projects. I keep in mind that even ‘major projects’, over time, start to feel like hard slogs. There are plenty of projects that are hard, long, tiring and draining. They reach a point when they might not be enjoyable. But (many) are necessary.

I try make sure that all the high effort projects I take on are important (or high impact) — it’s one way I stay motivated. I make sure that I don’t just ignore the ‘Hard slogs,’ I tell people why I’m not taking them on. Sometimes I can turn a ‘hard slog’ into a major project. I might be able to reduce the individual effort (by increasing the team size) or increase the impact by re-framing the architecture. IA is often a balancing act between requirements on the one hand and capability on the other. You can play a similar game with a ‘hard slog’ project. How might you change or re-frame the project to transform it into ‘major project’ territory? Think about the systems you could connect or improve — the concurrent architecture you can exploit or enhance. If you can’t do this, think hard about whether you should take it on.

I always try to balance the number of hard slogs and major projects I have. In the real world hard slogs aren’t avoidable — but take on too many and you’re not doing anyone any favours.

I also try to make sure that there are ‘quick wins’ in my portfolio. These give me the buzz of a tangible achievement and regular examples of the value that I add.

And I try to find a project that I love. I can turn to this at times when I’m having a hard day or week. This isn’t selfish. It will make you more productive. It will help relax your brain so that you’re better-able to do the “harder” stuff.

But that’s only one way of prioritising and making the most of your portfolio of projects — based on effort and impact. My second method relates to my final diagram — the futures cone. It introduces a way of thinking more strategically about your portfolio — or at least tricks the brain into overcoming the challenges I’ve described.

Futures cone

Futures cones helps us think about the future. The simple digram helps us visualise where we are now and a range of possible futures. Thinking through possible, plausible and desirable scenarios help me envisage the evolution of a design, system or service over time. It’s this ability to think of time as an extra dimension to my work that ties these three diagrams together and helps me to manage and prioritise my work.

The cone tells us a simple story that things evolve over time. We can make decisions today that make specific things more or less likely (and easier to do) in the future.

Overlaying a cone on top of the prioritisation matrix tells a simple story that the ‘quick wins’ of today could be the steps towards a major project.

Pace layers show how the elements of a design evolve at different rates. Our ability to affect the lower layers is slower-paced. We need patience to have an impact at the lower levels.

Thinking about the ‘major projects’ and ‘hard slogs’ as the evolution or cumulative result of many smaller interactions helps with motivation and flexibility. We can stop trying to “swallow the elephant” in one bite when we frame small tactical interventions into more strategic decisions. Decisions about projects can be made with reference to the scenarios we want to play out in the broader context. It can help us to ignore quick wins that don’t contribute to longer term goals. We start to see more ‘systems’ as we focus on the interplay and evolution of the smaller projects we can take on. It’s a simple way to become more strategic.

Architecture sits at the base of designs. It connects and constrains design at higher layers. It takes longer to create. For those of us based in large organisations, I suspect there’s always more work than there is capacity. So we stretch things over longer periods to achieve results. When we’re smart about this, we realise that we’ll only have an impact on the slower paced elements if we stick on the same track. We can plan evolution at the slower-paced layers and create an intentional architecture through the interplay between smaller, faster-paced elements. But we need patience and a plan.

Considering the pace, effort and impact and how each project contributes to the emerging broader architecture we can move more confidently into the future. These are the tools I use to manage my workload today to get the future I want.

Leave a Reply